First thing first: The artist Alex Plante has made a Rattini!! I saw her designs of raccoons eating dim sum and pigeons eating hot dogs, and I loved the vibe. I asked for a rat in a martini glass. Because all “rats” are in the taxonomic tribe Rattini. A “tribe” is what taxonomists put between a family and a genus when they have no idea what is going on. The shrug emoji of taxonomy. But of course I immediately thought of a rat-martini.

Alex did NOT disappoint. Look at this!

I adore the expression on its face, it’s like “I don’t know how I got in here and I don’t know how I will get out. But I have an olive, so….this is fine.” Anyway if you would like this glorious rattini you can have one! On a shirt! Or a sticker! Mine’s on the way and I can’t wait.

NOW, onward to today’s story.

The Seljuk merchant urged the wagons along. They were heading east, almost to the edge of the steppe in Eastern Anatolia, and the merchant was nervous. Mongol warriors had been sighted recently. Run into a band of those, you lose your goods. Sometimes your freedom. Sometimes your head. The wagons were carrying food, fine fabrics, wine. Plenty of things of interest to raiding bands. The hired guards were supposed to defend against bandits, of course, but Mongols were not just any bandits.

The man shrugged his shoulders, trying to shake the feeling that there must be something creeping up behind him. It was probably just his fears.

It wasn’t. His first clue was the thunder of hooves. The merchant train tried to hurry, desperate to run to the safety of the trees ahead, but oxen can only move so fast.

Within what felt like seconds of heart-pounding terror, the merchant was sprawled inelegantly on the ground, coated in dust. Opening his eyes, he faced a pair of bowed, armored legs. The merchant began to pray. This was the end.

The Mongol warrior unsheathed his sword, touching it gently, almost lovingly, to the merchant’s neck. The merchant opened his eyes, determined to face his death bravely. The warrior eyed him narrowly, and spoke.

“Nice hat.”

Obviously I made that up. But for the last few months, I’ve been on the trail of a hat (when times get hard, it helps to have a dissociative fixation. There are many like it. But this is mine). A historic hat so fashionable it was used to pay tribute—and no one now truly knows what it looked like.

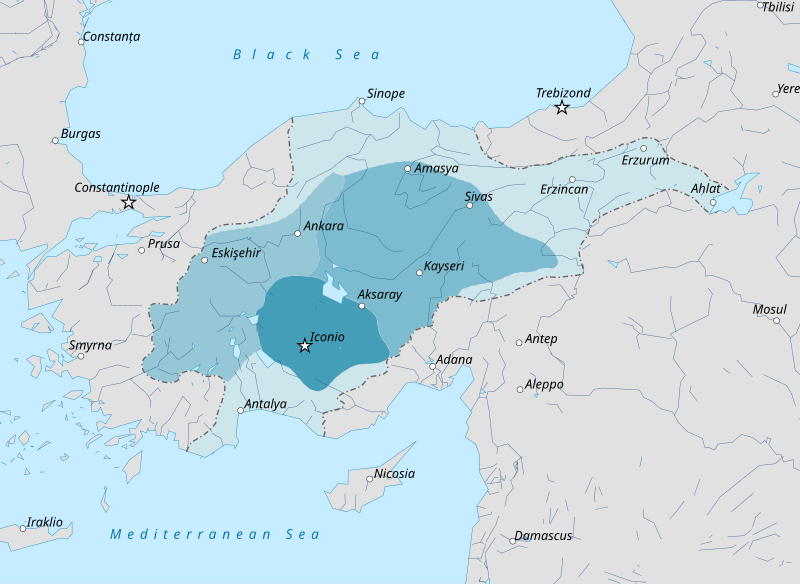

The year is 1259. The location: Eastern Anatolia, what is now western Turkey. This mountainous region was under the control of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rūm (This name never stops entertaining me) who had been gradually encroaching on the Byzantines to the west. But in 1241, the Mongols came riding out of the steppes, and the Seljuks never had a chance. The area fell in 1243. (If you want to know where the whole “pouring molten metal on someone til they die” came from, George R.R. Martin got it from the Mongols.)

Mongol conquerors didn’t always live in the places they conquered. They didn’t want to or need to. Their culture was nomadic, centered around their horse herds. Good grazing land was worth having. But the rest was good mostly as a tax base. They conquered because they had a mandate to do so, they believed they were the most superior culture on Earth*, and that the world should come under their dominion. For a while, they weren’t wrong.

So they’d conquer a place, and then extract tribute from it, a time-honored tradition across many cultures. In this case, in 1259, the Mongols asked for a yearly tribute of a lot of money, goods, and hats. 3,000 Turkish felt hats, to be precise.

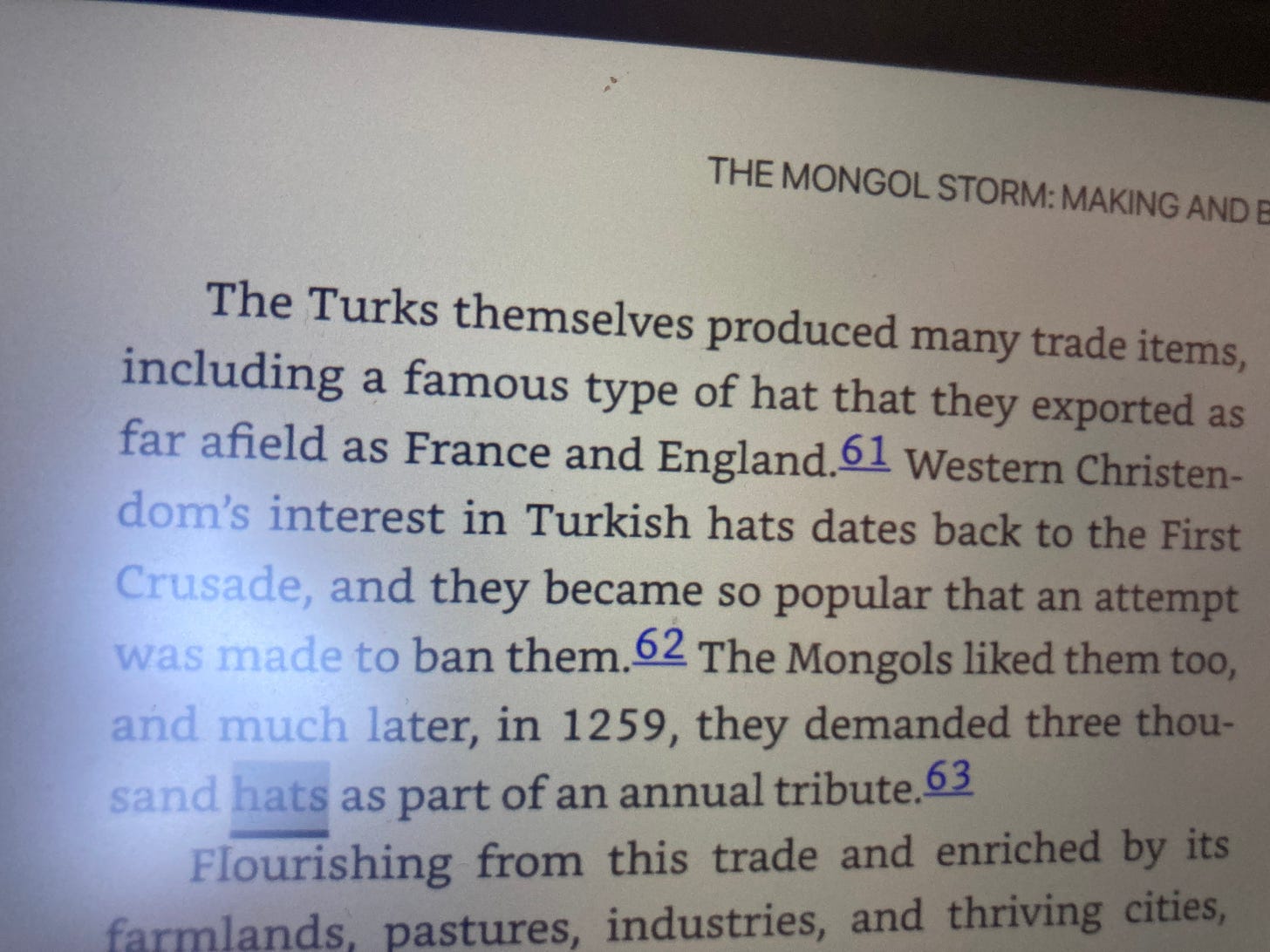

I heard about this while listening to the History of Byzantium podcast,** in an episode with the historian and author Nicholas Morton, about his book The Mongol Storm: Making and Breaking Empires in the Medieval Near East. Morton included this fun factoid about tribute hats in his interview, and I was instantly fascinated.

What was this hat? What is a hat SO COOL it ransoms 1/3 of a kingdom? This must be one heck of a hat, right? Morton mentioned it was made of felt. But there are lots of felt hats in the world.

Being a journalist means being unafraid to just start asking questions, even to people who might seem like they’d never give you the time of day. So I contacted the host of the podcast and asked about the hat. Robin said he thought perhaps it was a turban-like situation. I found this suspect, if the hat was felt, a turban seems like a very bad idea.

Of course, one should turn to the source! So I bought The Mongol Storm, and read it.

This will not do. I contacted Dr. Morton and asked him what the hat might have looked like. He said that, unfortunately, he didn’t actually know! He’s not a fashion historian (very reasonable!), and he got the fact from Jackson’s “The Mongols and the Islamic World: From Conquest to Conversion.”

I of course went right to the source.

The result:

“When Hülegü divided the Rūm Sultanate between the brothers ‘Iss al-Dīn Kaykāwūs and Rukn al-Dīn Quilich Arslan sixteen years later, in 657/1259, the aggregate annual tribute was fixed at 2,000,000 dinars, 500 pieces of silk brocade and Damascene cloth, 3,000 hats trimmed with gold filigree, 500 horses, and 500 mules.”

The citation is to Karim al-Din Aqsara’I (اقسرائی الدین کریم’)’s 1323 book, translated “Nighttime Narratives and Keeping up with the Good”, which was a general early Islamic history. Which…I don’t have access to and which appears to be only translated into Arabic from another language, possibly Persian, which was a common court language at the time.*** Ok the hats have gold stuff on….but what kind of hat?! Not described. COME ON.

Luckily, Morton had more info. He told me that in fact, the hats the Mongols liked were popular all over Europe for more than a century. In fact, at a church conclave in 1119, so many returning Crusaders were sporting these hats that the church tried to have them banned. This could have been simple xenophobia, but it could also mean the hats were ostentatious in some way. Perhaps tall or wide.

I was fixated now. This hat must have been very, very cool.

Morton gave me some ideas of where to look. He recommended looking at artistic depictions from the 11th-13th centuries, also recommended Peacock’s “The Great Seljuk Empire.” I also began to spread the hat story amongst my friends. Some of my friends are cosplayers, and suggested I contact people who might re-enact characters from that place and period. I started hunting historical cosplay.

Unfortunately, while there are some really awesome sources out there (like this one), I did not have luck with people getting back to me (in that particular case, the author has sadly passed away). So I turned to historical scholars, and started hunting up people who specialized in the art or fashion history of the Mongols in the 13th century. There are more of these than you might think. Boris Liebrenz, a historian at the University of Leipzig (who, when I contacted him, was working in Turkey), for example, wrote an entire paper on the tax receipts kept inside an ancient Seljuk hat (Sadly, he is an expert on the taxes, not the hat, but was a lovely person to talk to nonetheless).

One of the cosplayers, in her coverage of 12th century Seljuk fashion, noted, “A cap with a turned up brim (think of a baseball cap with the brim flipped up) usually edged in black (most likely silk).” I encountered this style again when I contacted Sheila Blair, professor emerita of Islamic art at Boston College. She sent me a 1995 article by Priscilla Soucek, who trained in Beirut and Turkey, on the “Ethnic depictions in Varqah ave Gulshah.” This is an analysis of the clothing and depictions in a stunningly illustrated manuscript from the 13th century, telling the story of Varqah and Gulshah.

WHO are Varqah and Gulshah? This is an 11th century Persian epic story about two cousins who fall in love. The cousins’ parents are chiefs of their tribe, and the two ask to get married, but Gulshah gets kidnapped and Varqah (a great warrior, obviously) and both their dads fight a big war to free her. Then Gulshah’s dad cancels the wedding (!) because Varqah is poor (but they all just fought this war so who exactly caused this problem?), so he goes off to make money in Syria. Meanwhile, Gulshah’s mom marries her off to the king of Yemen (Gulshah is fabulously gorgeous, obviously). Varqah gets back and hears Gulshah is dead! But he confronts this obvious disinformation and the king of Yemen. The king of Yemen, it turns out, is a really lovely man. Varqah realizes he can’t break up this marriage, and dies of heartbreak. Gulshah goes to his grave, and also dies of heartbreak (Varqah maybe you SHOULD have broken up that marriage). Finally, after years of being a site of pilgrimage, they are resurrected by the Prophet Muhammad and reunited. If you think this sounds a little bit like Romeo and Juliet or Pyramus and Thisbe, you are correct. If you think it sounds even MORE like Floris and Blancheflour, then you are a massive nerd, also correct, and 100% my type of person.

Anyway, in this manuscript there are multiple depictions of the Shah-i Sham, the king of Syria. And in all of them, he’s wearing a HAT. A hat that looks a lot like a baseball hat with a flipped up brim, edged in some kind of material.

It’s got designs and stuff, it seems like it would stick out a bit. It’s a nice hat. It’s A hat, but was it THE hat? MY hat? It might have looked something like this.

I continued hunting people, and came across Rachel Schine, a professor of History and Arabic at the University of Maryland, via Bluesky. We tumbled accidentally into conversation, and when I realized she was a Medieval historian somewhat near this area, I enthusiastically info-dumped about My Hat. She offered the idea that the had might be something like a kalpak.

The kalpak is the official men’s hat of Kyrgyzstan (a country burritoed by Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and China). But it’s been worn by Bulgarians, Ukrainians, Turks, Russians, Poles, basically anyone who has lived in Central Asia and toward Eastern Europe. The modern version worn in Kyrgyzstan looks like this:

It’s a tall-crowned hat, either vaguely square or conical, with a brim that can be flipped down or pulled higher, as the wearer pleases. It’s usually lined with fleece or felt, and can often be beautifully embroidered or filigreed.

Schine was not alone. I reached out to Patricia Blessing, a professor at Stanford who wrote “Rebuilding Anatolia after the Mongol Conquest: Islamic Architecture in the Lands of Rūm, 1240–1330.” She noted that a LOT of hats are called the kalpak, and they can vary widely. She recommended Eiren Shea, professor of Art History at Grinnell College, who wrote “Mongol Court Dress, Identity Formation, and Global Exchange.” Shea agreed that something “kalpak-like” could be it, and offered some demonstrations from her own medium: Medieval ceramics.

Interestingly, Schine noted to me that the kalpak had a pretty recent resurgence in the popular mind because Atatürk, the founder of modern day Turkey, liked to wear one and encouraged others to wear them too, considering them a part of the “Turkic ethnicity.” He liked to wear his with the brim pulled ALL the way up. Show off that fleece interior.

Sadly, Shea’s work focused on the EASTERN end of the Mongol Empire (aka, near modern China), and so she recommended me to Bermet Nishanova, a grad student at UV Irvine who is currently on Fulbright in Uzbekistan. Her project? Medieval Islamic textiles!

Nishanova noted that finding THE hat would be tough. And of course, it’s probably more than one kind of hat. This was 1259, Shein didn’t exist, each of these hats was being handmade, probably by many people in many different styles. She also noted that there were a LOT of different styles of hat that varied regionally. Most of them were kind of tall, conical-ish, and lined. But fabric is a really tough thing to preserve, especially in places like the steppes of Eastern Anatolia, where it’s hard to preserve basically anything.

Of course at this point you might be wondering: Why HATS!? Why did Mongols want hats? Why not…prisoners or food or land or anything else?

And the answer is that the Mongols often demanded textiles, including hats, in their tributes. If you’re a mobile culture, like they were, this makes a lot of sense. They couldn’t display their wealth in big fancy castles or mosques, they had little use for buildings that stood in one place (though they did build several capital cities, they often traveled between them). Valuable stuff to them was mobile stuff! What’s mobile? Fashion. So throughout ancient nomadic empires, you’ll find remnants of fancy textiles, from very expensive Persian rugs (which have ALWAYS been in fashion), to swank silks (and velvets when those were finally invented), to hats!

Mongols were a hat-wearing sort of people. They spent a lot of time on horseback on the steppe, exposed to the elements. Hats are useful things to have, and having a lot of nice ones is an indicator of status. Furs and wool were expensive. Liebrenz pointed out that “if the aim was to outfit an expansive court elite, probably give them out with the robes of honour, that seems absolutely logical.”

But of course, we all could be wrong! The hats could have looked completely different. As many of the historians told me, textiles generally don’t get preserved well, they break down, get torn, lost. As Peacock pointed out in The Great Seljuk Empire, there are also a lot of sources that we in the West can’t READ (as the one I encountered that was probably in Persian). I did hear from people who were Turkish, who had studied in Turkey or in Central Asian countries, but unfortunately, many of the original sources still haven’t been translated, even into modern versions of the original ancient languages.

So My Hat could have been the first one with the flipped up brim, the proto-kalpak, or just a tall, embroidered conical hat with no brim. It could have been a mix, or something else entirely.

It’s both fascinating, and frustrating, to realize that we may never know! We, the non-historian public, tend to have pictures in our heads of what people must have looked or dressed like in history, based on art or media. But many of those pictures are based on very specific examples of historical art. Some of those were things like symbolic church effigies, tapestries depicting great events, or stylized ceramics. At best, those would depict the fanciest of people of the time, in their best ceremonial stuff. In that case, our vision of the past might end up being like if every modern person was walking around in clothes right off the runway. At worst: Most of the people making tomb effigies and tapestries probably never even saw the people they were depicting. These drawings could be the fantasy version of fashion. Like if every modern person was walking around in clothes photoshopped on like models on fashion websites, click to change the shirt!

But it’s also fascinating to take a deep dive into something relatively small. To realize even then, in the 13th century, people cared about fashion a great deal. As much as we do now. So much, that 3,000 hats could buy the safety of a kingdom. For a little while, at least.

The Seljuk merchant shaded his eyes, staring to the East. Here he was, in the same spot as before. A few years older, and many experiences greyer. Now, he was part of a massive train, lined up on the edge of the steppe. The wagons groaned under the weight of money and fabrics. Herds of animals shuffled and snorted. All of it tribute, safety purchased from the Mongols.

A dust cloud in the distance slowly resolved itself into a large detachment of warriors, and a vast train of empty wagons. The leaders rode slowly forward, trailed by secretaries and bureaucrats, here to keep careful count. The merchant, stepping forward gingerly with his group, offered up an example of his goods. A tall-crowned hat, gold-embroidered, lined in felt. The situation wasn’t ideal, but the merchant still took pardonable pride in his sourcing. This was a hat, he felt, any courtier would be pleased to wear.

The leaders of the Mongols stepped forward, and one approached, looking down at the merchant, who glanced up, and stared. He, too, was older, with creases around his eyes. But the face was the same, the face seared into the merchant’s memory by the feeling of a sword at his neck. But this time, there was no sword. Instead, the Mongol warrior, clothed in expensive silks and brocades, looked down at the merchant, and winked.

“Nice hat.”

References

One of the best things about this recent hat obsession has been how many historians got back to me! A science journalist who admitted she just had a weird interest in hats! Most of the historians I contacted got back to me within 24 hours, and often with links, attachments, speculations. It was truly lovely. Thanks so much to Rachel Schine, Eiren Shea, Bermat Nishanova, Patricia Blessing, Sheila Blair, Boris Liebrenz, and Nicholas Morton. And to Robin Pierson for his great podcast, I learn a ton.

Peacock, ACS. “The Great Seljuk Empire” Edinburgh University Press 2015

Soucek, P. “Ethnic depictions in Varqah ave Gulshah.” Presented at the 9th International Conference of Turkis, 1995.

Jackson, P. “The Mongols and the Islamic World: From Conquest to Conversion” Yale University Press, 2017.

Morton, N. “The Mongol Storm: Making and Breaking Empires in the Medieval Near East” Basic Books, 2022.

Dietrich, R. “Seljuks Cultural History.”

Tackett, Dinah. “Pre-Mongol Persian Costume Or 11th and 12th Century Seljuk Dynasty Costume” 2013.

Head of a Central Asian Figure in a Pointed Cap. (12th–early 13th century). [Gypsum plaster; modeled, carved]. In Head of a Central Asian Figure in a Pointed Cap [42.25.17]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://jstor.org/stable/community.18505921

Top Section of a Water Jug, late 12th–early 13th century. Ceramic; earthenware, pierced decoration, 12 x 14 1/4 x 14 1/4 in. (30.5 x 36.2 x 36.2 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of The Roebling Society, 73.30.6. Creative Commons-BY

S.S. Blair, A Compendium of Chronicles. Rashid al-Din’s Illustrated History of the World, The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, volume XXVII, London 1995.

J.M. Rogers, The Arts of Islam. Masterpieces from the Khalili Collection, London 2010, cat.180–97, pp.156–65.

Where have you been?

Is it reading Elizabeth Preston’s new newsletter? Like all her writing, it’s informative and adorable. She gives advice to crabs and cuttlefish!

Maybe it’s reading about the first farmers. I’m not talking about the Levant. I’m not talking about China. I’m talking about ANTS. 66 million years ago. By Riley Black.

Maybe it’s watching this AWESOME video on how riflebirds sound like…a rifle. It’s not how you think.

A lady has been feeding raccoons for years, and then called 911. Why? 100 raccoons showed up in her yard. You fed around, you found out.

New Jersey has instituted a black bear hunt. If this horrifies you, many states, including PA, never stopped having one. And if it STILL horrifies you, make sure the black bears near you have no human food options. Because that’s why this hunt is takin place.

Where have I been?

You can hear me talking about pests, and whether or not it’s a word that should even exist, on the Beyond Organic Wine podcast.

I also have a Halloween-themed piece on werewolves and the moon! Werewolves, hear me out. Tired: Full moon. Wired: New moon. Inspired: Changing your shifting time based on your position in the food web.

My latest Scientific American column is on hair! Specifically whether the hair on your head swirls clockwise or counterclockwise, and whether the Coriolis effect has anything to do with it. Spoiler: No.

Anti-Discourse Actions

The internet has become nothing but a firehose of information and rumor and fear and hate. Logging on to social media has yet to make me feel good. What does? Taking action.

Now’s the time. I’m going to VOTE. And because it’s legal in my state to support election workers, I’m dropping off baked goods at my polling place (I know several of the people there, they live in my neighborhood, because voting is LOCAL) to let them know they are valued.

Make a voting plan. Research your candidates. Vote.

*My favorite bit of this is that the Mongol culture was shamanistic, and centered around a creator in the sky. Numerous Christian and Muslim clerics tried to come and convert them en masse, with very little success. Because the Mongols believed that they were the most superior, their religion was also the most superior, and they patted these clerics on the head with great condescension for their little gods. As someone who has suffered from missionaries all my life, this gives me a great deal of grim satisfaction.

**I listen to a lot of history podcasts. I don’t know why but dudes reading history in soothing voices is very relaxing. We’ve all got weird stuff okay. And yes, I’m very well acquainted with Mike Duncan’s work. He’s a boss. I also like The British History Podcast, Tides of History, The History of China, History of Africa, History of English, Stuff you Missed in History Class…you get the idea.

***I spent more than $100 on this hunt just on books and articles, so you’ll have to forgive me for not hunting down a translator.