Bailey Herring, 16, is standing outside the auction, tears streaming down her face. She traveled to Chincoteague, Virginia, all the way from San Pierre, Indiana to be here today. She had her mother, a trailer, and $2,000, carefully saved from summer jobs.

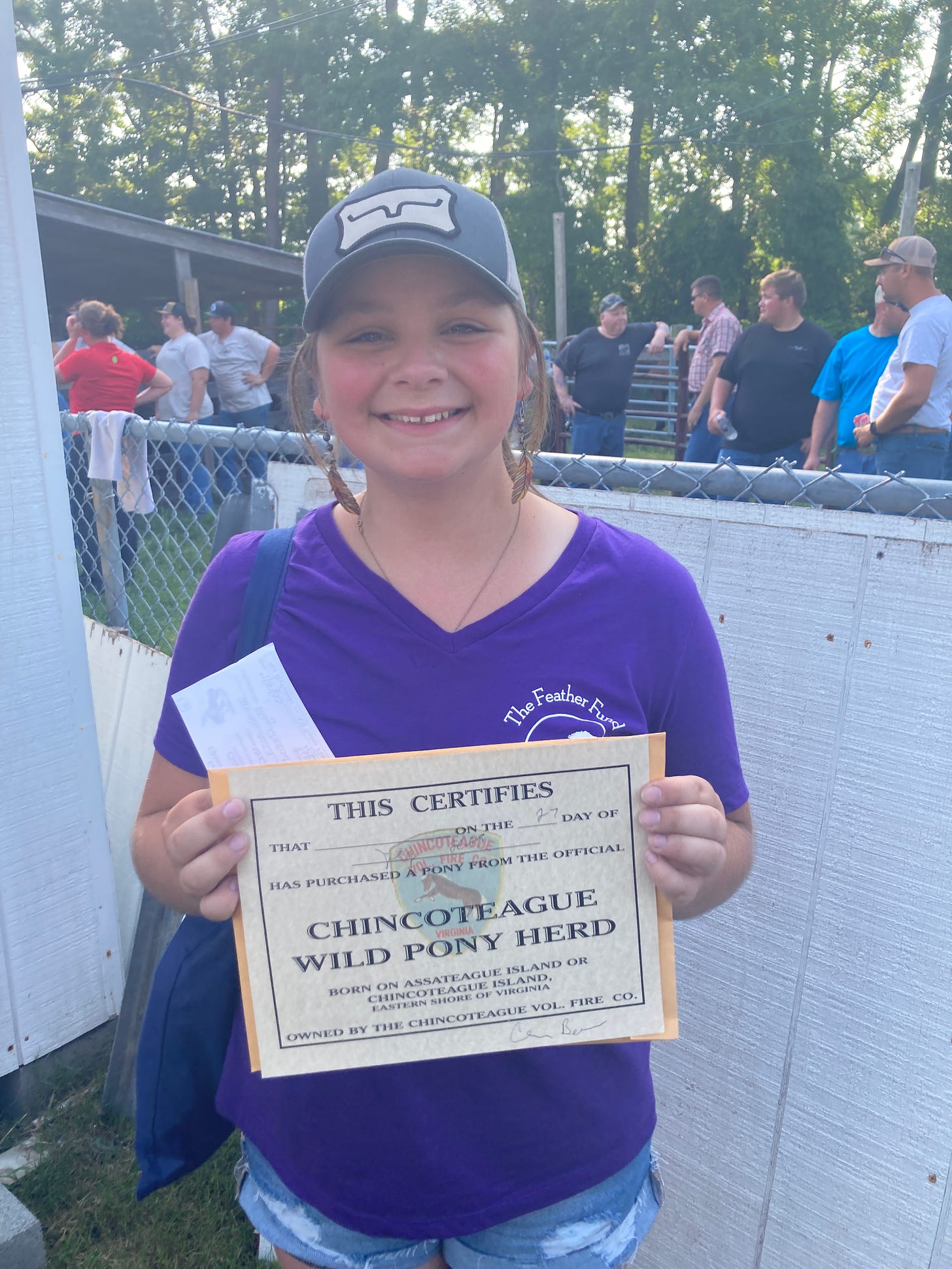

Now she’s standing in a bright purple T-shirt outside the auction, sobbing with joy. She’s the proud owner of foal #6, a brown and white pied filly with a tufted little mane. Her own Chincoteague pony, that’s she’s already decided to call Tallulah.

“I’m still shaking,” she says. “I can not believe I got it.”

The process of bringing Bailey and Foal #6 together has been a long one. On Bailey’s end, she applied to the Feather Fund, a nonprofit that raises money to help deserving kids (thus far, all girls) to purchase their own Chincoteague pony at the yearly Chincoteague Pony Swim. Bailey wrote an application, complete with plans for how she would care for her pony, her experience with horses, how the horse would be transported, and signatures of permission from her mother. She also included a passionate essay which included how much she had researched the breed, and how much owning one would mean to her, “everything and anything that I could say,” she says.

The application was due in April. Now, it’s July, and Bailey’s dream came true. The $2,000 that Bailey has saved is not for the horse, but for its food and housing. The actual price of the pony—$7,200—was paid for by the fund.

For Foal #6, the road has been far longer. She was only born the previous fall. But she, and her mother and father are part of the “Chincoteague Wild Pony Herd,” a group of around 150 ponies that run free on the Virginia island of Assateague. A smaller herd of about 75 runs on the Maryland side of this long barrier island, separated by a fence from their southern cousins.

Every July, the Virginia ponies are rounded up by “saltwater cowboys”— men, and a few women, all members of the Volunteer Fire Company of Chincoteague —who ride their own horses over on barges to Assateague. They herd the wild ponies into pens, where they are checked over my veterinarians and get some vaccines.

The next day, rain or shine, the ponies are gathered on the shore, and at slack tide, the saltwater cowboys begin cracking whips and shouting, herding the ponies toward the water. The herd swims across the small saltwater inlet between Assateague and its nearby island of Chincoteague. They are swimming toward their fans. Thousands of people come every year to see the Pony Swim, made famous by the 1947 book Misty of Chincoteague (so famous, you can go see her taxidermy). There are so many people standing on the shore, yelling and waving and taking pictures, that I was surprised the whole island didn’t tilt.

Because yeah, I was there!

I was there to cover the pony swim for Sierra Magazine. Over three days I spoke to tons of people about the ponies on both the Maryland and the Virginia side, asking about their history, and why exactly people feel so very strongly about them. Of course I ended up with far, far more material than a single 1,000 word story could come close to fitting. Luckily my kind editor told me I could put the rest here!

Which is so awesome, because I’ve got SO much to say.

I learned so much that week, about the ponies, but also about what people believe about them. Why they love the Chincoteague ponies so much, and what that love means for the lives of that small herd.

Because Bailey was not the only person who went home with a horse that day. The day after the swim, the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Company auctioned off 72 foals in 2023. Seven were auctioned specifically as “buy backs,” which means the people buying the pony will never own it. They will never even touch it. They get to give it a name, and then that foal will go back to Assateague with its herd, to continue the line of the Chincoteague ponies. If you think $7,200 is a high price for a pony, don’t even think about a buy back. This year’s highest price pony was a buy back, and fetched $43,000.

Bailey plans to show Tallulah when she’s old enough. She already has a mini horse and a quarter horse. But she’s always wanted a Chincoteague pony. Ever since her grandmother showed her any article about the horses. “I absolutely fell in love with the idea that they swim, they were wild ponies, and they swam over and then you can buy a baby, [it] was amazing,” she says. The ponies are more than just horses, Bailey says. There’s a feeling. A feeling that you can buy something wild, something free, and it will be yours.

But are these ponies wild? Are they free? What are they even doing on a salty barrier island off the coast of Virginia? Horses, you see, are not native to Virginia. Far from it. And yet, these horses roam as protected individuals across state parks and National seashores. And we follow along behind them—ripping up and culling the invasive species that live there with them.

Who are these horses? And what does our love for them say about us?

In the next few newsletter installments, we’re going to talk about it. I’m breaking it up, because the last thing you need in your inbox is another 9,000 word essay. So next time, I’ll go into what is it to be a “wild” pony on Assateague, and how wild that really is.

Don’t worry, there’s lots more pony pics.

Where have you been?

And is it reading about TURKULES (rhymes with Hercules)!? This story of an attacking turkey is delightful, especially the number of people who approach it with love, only to stare war in the beak.

Is it reading about how kingfishers dive to catch fish and smack into the water at 40 miles an hour and somehow don’t get concussions?! How do they do it?! Pointy beaks, and potentially tough brains. And moxie of course. Lots of moxie.

Is it reading about bird names are going to change, so we no longer honor the legacy of dead white (usually racist) guys? I personally think this is a great opportunity to give the birds all names that make them feel good about themselves.

Where have I been?

This week on the podcast, I’ve been talking with Rachel Nuwer about her latest book “I feel love,” about the promises and history of ecstasy.

And speaking of the podcast, we’ve decided this is our last year. We’ll be heading into the sunset at the end of 2023. It’s been a good, nearly 15 year run, but it’s just time for us to move on. Don’t worry, the back catalogue will remain! And we’ve got a few more eps waiting in our back pocket.

Stay tuned! Because we are HORSING AROUND.

Awesome article! 💜 Just one correction... the Feather Fund has purchased ponies for three boys, so it's not just girls. But it's definitely mostly girls! (Girls send in most of the applications.) Thanks for writing an awesome article!

💜

Lois Szymanski,

Chincoteague Pony book author